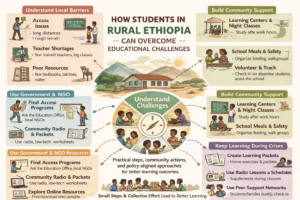

How Students in Rural Ethiopia Can Overcome Educational Challenges

Practical steps, community actions, and policy-aligned approaches for better learning outcomes

Education in rural Ethiopia has improved markedly over recent decades, but students outside towns and cities still face a web of challenges: long distances to school, shortages of trained teachers and textbooks, weak school facilities, seasonal poverty, and periodic crises (drought, displacement, or health shocks) that interrupt learning. The Federal Ministry of Education’s current sector plan recognizes these gaps and sets priorities for equity, quality, and access—but families, teachers, communities, and students themselves also play critical roles in turning policy into day-to-day progress. Below is a practical, step-by-step guide for how rural students (and those who support them) can overcome barriers and build learning resilience.

1. Understand the main barriers (so you can act on them)

Before you fix anything, be clear about the biggest problems in your area:

-

Access and distance. Many children must walk long distances or cross difficult terrain to reach school; this reduces attendance and increases dropouts during bad weather or busy seasons.

-

Teacher shortages and training gaps. Rural schools often have few qualified teachers, heavy multi-grade classes, and limited professional development.

-

Learning materials and infrastructure. Textbooks, classroom furniture, latrines, and water are often insufficient—all of which undermines learning and attendance.

-

Poverty and opportunity costs. Families sometimes need children to work in the fields or care for siblings; early marriage and seasonal migration also interrupt schooling.

-

Weak continuity in crises. Emergencies (droughts, conflict, and health crises) cause extended school closures and unequal remote-learning capacity.

Knowing which of these is most acute locally helps you choose the most effective interventions.

2. Practical actions students and families can take

These are low-cost, high-impact steps students and families can implement immediately.

Prioritise regular attendance and small routines

-

Create a simple daily routine (study time, chores, rest). Even 30–60 minutes of focused study each day adds up.

-

Buddy up: two or three students study together and hold each other accountable. Peer support reduces dropouts and improves reading practice.

Use available materials creatively

-

If textbooks are scarce, form a rotating book club where families pool photocopies or borrow from nearby schools.

-

Make low-cost flashcards from scrap paper for vocabulary, numbers, and facts; use them while walking to school.

-

Convert household chores into learning: measuring for recipes = math practice; telling family stories = language skills.

Build basic learning spaces at home

-

A small shaded corner with a mat and a lamp (solar lantern if electricity is unavailable) becomes a predictable study spot.

-

Limit distractions during study time—phones, loud radio, or noisy chores—by negotiating a short “quiet hour” with family.

Negotiate flexible roles with caregivers

-

If children must help with work, agree on specific hours for schoolwork or weekend catch-up sessions. Even small, predictable study blocks matter.

3. How teachers and schools can help students overcome rural challenges

Teachers and school leaders have outsized influence—here are pragmatic, low-cost strategies:

Multi-grade, clear micro-lessons

-

Structure short, repeatable micro-lessons (15–25 minutes) that can be reused across grades. This makes multi-grade teaching manageable and consistent.

-

Use local examples and mother-tongue explanations to ground abstract concepts.

Resource sharing and community involvement

-

Schools can coordinate with nearby schools to share textbooks, teacher training sessions, or seasonal learning camps.

-

Invite parent volunteers for classroom support, repair work, or to supervise reading corners. Community ownership increases attendance and protects assets.

Track attendance and early warning

-

Keep a simple attendance chart and follow up quickly with families when students miss several days. Early re-engagement prevents dropouts.

4. Community and local solutions that work

Local collective action often beats top-down answers because it is faster and context-sensitive.

Community learning centers and evening classes

-

Convert an unused room or shelter into a community learning center for remedial lessons and adult literacy—ideally with volunteer teachers or older students running sessions.

-

Evening classes allow children who work daytime jobs to continue learning.

School feeding and incentives

-

If possible, organize community meals or collaborate with NGOs to provide mid-day meals; this improves nutrition, attendance, and concentration. Evidence from across Ethiopia shows feeding programs increase enrollment and retention.

Local transport or group walking systems

-

Where distances are the main problem, communities can organize small groups or rotate a local minibus or cart to transport children. Even a community rota for walking with younger children improves safety and attendance.

5. Make use of government programs and online resources

The Ministry of Education’s sector plans and NGOs offer programs and resources to help rural learners—find and use them.

-

Connect with local education offices. Ask about transfers of textbooks, teacher training sessions, and any conditional cash transfers or bursaries. The National Education Sector Development Plan prioritizes equity for remote and pastoralist communities; local offices often have targeted supports.

-

Use community radio and low-tech distance learning. When internet access is limited, radio lessons and printed take-home packets have been successfully used in remote Ethiopian communities. During COVID-related disruptions, such approaches protected learning continuity.

-

Explore LearnEthiopia and similar portals. Online platforms provide exam practice, study guides, and scholarship notices. Even if the internet is intermittent, family members or school coordinators can download and print useful materials when connectivity permits.

6. For older students: planning pathways to income and higher learning

When families worry that school doesn’t lead to income, students are likelier to drop out. Connect schooling to future opportunities:

-

Vocational skills + schooling. Learn a trade alongside schooling (tailoring, agriculture techniques, mechanics) so study time produces near-term household value.

-

Scholarship and exam preparation. Use platforms and community study groups to prepare for secondary-entry exams; sharing exam guides and question banks reduces individual costs. LearnEthiopia and other services post scholarship openings and practice tests.

7. Resilience during crises: keep learning when schools close

Periodic crises are part of life in many rural areas. Preparing for continuity reduces learning loss.

-

Agree on learning packets (printed exercises) that students can complete at home; older students can mentor younger ones.

-

Establish radio schedules and a local plan to disseminate lessons and assignments during disruptions.

-

Use peer networks to maintain motivation: daily SMS check-ins, community noticeboards with weekly learning tasks, or study-buddy phone calls.

8. Advocacy: how students, families and communities can push for systemic change

Long-term improvements need better funding, trained teachers, and infrastructure. Communities can:

-

Organize regular meetings with school management and local education officials to request targeted services (e.g., latrines, textbooks, teacher postings).

-

Collect simple data—attendance lists, broken facilities, or a log of absent teachers—and present it at parent-teacher meetings or to local administrators. Evidence-based advocacy gets results.

-

Partner with local NGOs or religious organizations for small capital projects (a classroom roof repair, a latrine, or solar lights).

9. Simple checklist for students and caregivers (action list)

-

Set a daily study time (even 30 minutes).

-

Form a 2–4 person study group.

-

Keep one exercise book and a list of weekly goals.

-

Ask the teacher for one small extra task each week.

-

Parents: negotiate short, predictable study blocks around chores.

-

Community: Organize a monthly book/bundle swap and an attendance follow-up roster.

Conclusion—small steps, collective effort, and steady pressure

Policy frameworks from the Ministry of Education set the stage, but progress in rural areas is made through countless small, local actions. When students create routines, families support predictable study time, teachers use practical multi-grade methods, and communities organize resources (books, food, transport), learning improves quickly and sustainably. Combine those local efforts with outreach to government programs, and rural students can close gaps in achievement and opportunity. The path is incremental, but consistent community action—backed by the resources and plans already identified at the national level—produces measurable change.